Embracing intersectionality in science - Alma Levant Hayden's legacy in chemistry and drug safety (Chapter 16)

- Dr Audrey-Flore Ngomsik

- Dec 11, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2024

Alma Levant Hayden was a trailblazing chemist who left an indelible mark on drug safety and public health in the United States. Her story exemplifies the power of intersectionality in science and its crucial role in driving innovation and sustainability.

A childhood of curiosity and determination

Born in 1927, growing up in the segregated South, Hayden refused to let barriers stop her scientific curiosity. Despite facing significant obstacles as a young African American girl, she was driven by an intense passion for understanding the world around her. Her determination to learn and explore would become the cornerstone of her future scientific achievements.

Embracing science as a career

Hayden's journey into science began at South Carolina State College, where she graduated with honors in 1947.

She initially wanted to become a nurse but discovered a passion for chemistry that she

"just didn't want to part from". [1]

This passion led her to pursue a master's degree in chemistry at Howard University, where she studied under renowned chemist Dr Lloyd Noel Ferguson, one of the founders of the professional organization for the professional advancement of black chemists and chemical engineer.

Despite facing significant barriers as both a woman and an African American in the scientific community, Hayden persevered.

Her determination and intellect allowed her to overcome the prejudices of the time, which often saw women and minorities excluded from scientific careers.

She studied at the University of Howard, in Washington D.C., one of the most distinguished Universities of the USA, not sectarian but open to all sexes and races,[2] and obtained her master’s in chemistry. She specialised in infrared spectroscopy.[3]

Infrared light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The human eye cannot see it, but humans can detect it as heat.

Infrared Spectroscopy is the analysis of infrared light interacting with a molecule.

What is infrared spectroscopy?

Imagine infrared spectroscopy as a detective tool that helps scientists "read" the identity and structure of molecules. Think of it like a molecular fingerprint scanner.

Here's how it works:

Every molecule is made up of atoms that are constantly vibrating and moving, kind of like tiny springs connected to each other.

When infrared light (which is heat energy we can't see) passes through a sample, these molecular "springs" absorb specific amounts of that light based on their unique structure.

It's similar to how each musical instrument has a unique sound, even when playing the same note. Just as you can identify a trumpet or a violin by its distinctive timbre, scientists can identify molecules by the specific way they absorb infrared light.

Practical applications are everywhere:

Chemists use it to identify unknown substances

Forensic scientists analyze crime evidence

Environmental researchers detect pollutants

Pharmaceutical companies check drug purity

Food scientists examine the composition of ingredients

For example, if you wanted to know exactly what's in a mysterious powder or liquid, infrared spectroscopy could help you break down its molecular components without destroying the sample.

It's like having a super-powerful microscope that can see the invisible "dance" of molecules, revealing their secrets through the way they interact with light.

Alma Levant Hayden: an accoumplished scientist

In the mid-1950s, Hayden joined the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services responsible for safeguarding public health through the regulation of food, drugs, and medical devices.

Her appointment was a significant achievement, particularly given the FDA's reluctance to hire African American scientists at the time.

This hesitancy came from concerns that their testimony in court cases might be disregarded or prejudice proceedings due to racial bias, especially in certain parts of the country.

Despite these institutional barriers, Hayden's expertise and qualifications secured her position, marking a pivotal moment in the agency's history.[4]

More, Hayden became Chief of the Spectrophotometer Research Branch in the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry in 1963.[5]

She worked with her colleagues on chromatographic techniques to characterise adrenocortical steroids in urine.[6]

The main role of adrenal steroids is to regulate electrolyte and water levels in the kidneys.She also worked on characterising barbiturates and sulfonamides from paper chromatograms.

Barbiturates are sedative drug used to relax the body and help people sleep, they were popular at the XIXth century at sleeping pills or recreative drugs.

Sulfamides are an antibacterial agents.She has published 17 articles in renowned journals.

Changing the World: The Krebiozen investigation

Before talking about the Krebozien investifation, you should know about the thalidomide scandal and the Kefauver-Harris Amendment.

The thalidomide scandal and the Kefauver-Harris Amendment

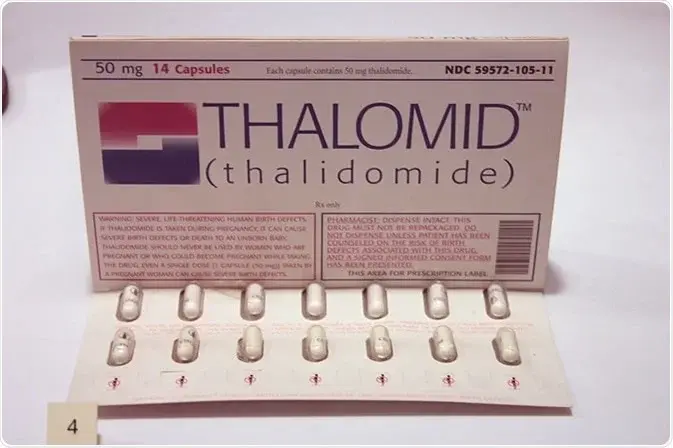

In the late 1950s, thalidomide, a non-barbiturate sedative was advertised as safe for everyone, including pregnant women.

Future mothers used to take the pill to prevent morning sickness.

It was an over-the-counter drug sold in 46 countries, in the early sixties, as popular as aspirin.[7]

This medication caused thousands of mothers to give birth to disabled babies.

Miscarriages happened, limbs failed to develop properly, in some cases also eyes, ears and internal organs.

No-one knows how many miscarriages the drug caused or how many worldwide victims of the drug there have been, but it's estimated that, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a range from 10,000 to 20,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities.[8]

This tragedy led to a revolution at the FDA regulatory authority: the requirement that all new drug applications should make a proof of efficiency for the targeted market application and should prove their safety for the consumer.

This change called the Kefauver-Harris Amendment is the start of the FDA approval in its modern form and is the reason why bringing new drugs to the market is such a long and difficult process. [9]

We will talk about the women who saved America from a generation of "thalidomide babies" in a future article.

The Krebiozen investigation

Following this tragedy, in 1963, Alma Hayden, then Chief of the Spectrophotometer Research Branch in the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, had to deal with major medical controversy.

In 1940s, Dr Andrew Invy and Dr Stephan Durovic claimed that to have discovered a new drug derived from distilled blood serum of horses, called Krebiozen, able to cure cancer.

In 1963, Hayden and her colleagues were assigned the task to determine what the drug was and whether it had any therapeutic benefits in treating the disease.

Using infrared spectroscopy, and comparing images of over 20,000 known substances, Alma Hayden and her team analyzed Krebiozen and discovered that it was nothing more than creatine, a common amino acid derivative already found in the human body. [10]

This revelation exposed the fraudulent claims surrounding the drug and protected countless cancer patients from exploitation.

“By the fall of 1963, FDA had reached its scientific conclusions. The Krebiozen powder, the agency announced, had been identified by several chemical tests as creatine.

The contents of Krebiozen ampules were identified as mineral oil, with minute amounts of two other substances, amyl alcohol and 1-methylhydantoin, found in ampules shipped in 1963.

FDA’s chemical analysis was soon supported by the findings of the National Cancer Institute that Krebiozen ‘does not possess any anticancer activity in man.'” [11]

Ivy and Durovic were brought to trial in 1964.[10]

Despite her irrefutable evidence, Hayden encountered resistance from Krebiozen's passionate supporters and manufacturers. The drug's defenders claimed there was a conspiracy to keep it off the market, and newspapers demanded "Real Hope To Cure Cancer".

When the case went to trial in 1965, Hayden was one of 179 witnesses who testified, presenting her findings amidst a highly controversial and emotionally charged atmosphere. he defense exploited the jury's lack of scientific expertise, sowing doubt about the precision of her methods. Ultimately, despite Hayden's clear evidence and testimony, the jury shockingly acquitted the defendants, demonstrating the uphill battle she faced in convincing the public of the truth behind this medical scam.

Recognition and legacy

While Hayden's groundbreaking work did not receive widespread recognition during her lifetime, her contributions to regulatory science and public health protection were significant. She testified at the criminal trial of Krebiozen's promoters, demonstrating the crucial role of scientific evidence in law enforcement.

Today, Hayden is remembered as a pioneer who paved the way for future generations of women and minorities in science.

Alma Levant Hayden died at 40 years old of liver cancer.

Intersectionality: the key to innovation

Hayden's success can be attributed, in part, to her unique intersectional perspective. As an African American woman in a field dominated by white men, she brought a multifaceted approach to her work. Her experiences likely heightened her awareness of the importance of rigorous scientific standards and ethical considerations in protecting public health.

This intersectionality allowed Hayden to challenge conventional thinking and apply a more holistic approach to drug safety. Her background as a member of marginalized communities may have contributed to her dedication to exposing fraudulent treatments that often preyed on vulnerable populations.

Parallels with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Hayden's story offers valuable lessons for modern Corporate Social Responsibility practices:

Ethical decision-making: Her commitment to exposing the truth about Krebiozen, despite potential backlash, exemplifies the ethical backbone necessary in CSR.

Scientific rigor: Hayden's insistence on thorough testing mirrors the need for companies to base decisions on solid evidence and research.

Protection of vulnerable populations: Her work in exposing fraudulent cancer treatments aligns with CSR's focus on protecting consumers and ensuring product safety.

Diverse perspectives: Hayden's unique background contributed to her innovative approach, highlighting the value of diversity and inclusion in corporate decision-making.

Conclusion

Alma Levant Hayden's life and work underscore the critical role of intersectionality in scientific innovation and its parallel importance in corporate social responsibility. Her legacy continues to inspire scientists and business leaders to embrace diverse perspectives, maintain ethical standards, and prioritize public health and safety in their pursuits of progress and sustainability.

This article is part of a series "Embracing intersectionality in science: the key to innovation and sustainability".

Comentarios